Florida Fish Farm Offshore Faces Opposition

|

Rob Hotakainen, E&E News reporter Greenwire

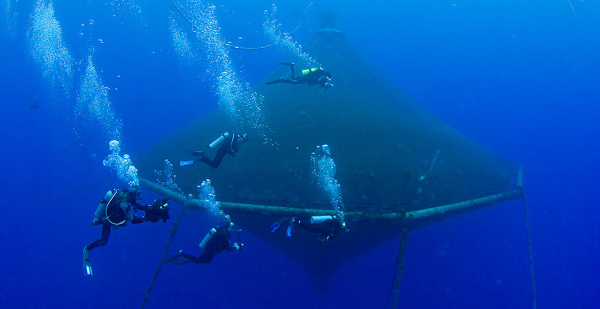

Divers outside one of the enclosures holding almaco jack at a fish farm off Hawaii's Big Island. Kampachi Farms has proposed to open a fish farm 40 miles off Florida's coast. David Fleetham/VWPICS/Newscom

If Neil Anthony Sims gets his way, he'll make history by opening a fish farm 40 miles off of Florida's west coast, where his company will begin raising 20,000 almaco jack fingerlings in a floating pen 130 feet below the surface of the Gulf of Mexico.

While aquaculture in state-controlled marine waters is nothing new, Sims' Velella Epsilon project would be the first of its kind in federal waters that extend between 3 and 200 miles off the coast.

If he can line up all the necessary permits for the pilot project by early this year, Sims said, he'll have the fish in the water by July or August.

"Hope is a thing with feathers, but that's the aspiration," said Sims, a marine biologist and CEO of Kampachi Farms, a Hawaii-based aquaculture company that proposed the project. "We felt we were perhaps best equipped to pioneer the permitting pathway in the Gulf of Mexico."

A big test will come tomorrow, when EPA hosts a four-hour public hearing in Sarasota on a draft permit for the fish farm.

EPA will hear testimony at the Mote Marine Laboratory & Aquarium's WAVE Center on whether to allow the company to discharge wastewater into the Gulf.

Opponents plan to demonstrate at the site an hour before the hearing. They want to block the project, claiming it would yield too much pollution and damage to both the U.S. fishing and seafood industries.

Shrimpers, for example, say they've already had to face too much competition from fish farms in India and Vietnam.

"We're fighting imports now from aquaculture with these damn shrimp farms, and they're killing us on prices," said Acy Cooper, president of the Louisiana Shrimp Association. "The only ones who are going to benefit from that are the people who are going to do it, and that's a problem — it's not the American public. It's just too hard for the domestic industry to make a living at it anymore."

Critics also fear the project would set a dangerous precedent that would only lead to more fish farms and more possibilities for environmental emergencies, like the 2017 spill of more than 260,000 nonnative Atlantic salmon into Washington state's Puget Sound.

On Capitol Hill, they've found a friend in Alaska Republican Rep. Don Young, who's pushing a bill that would block federal agencies from approving any aquaculture facilities in federal waters unless Congress first passes a law allowing it.

When Young introduced his bill, H.R. 2467, the "Keep Finfish Free Act," he said it would protect his state's wild fish stock from genetically modified species, and he argued that Congress should stop "the unchecked spread of aquaculture operations by reining in the federal bureaucracy."

"It's up to us to ensure that our oceans are healthy and pristine," said Young, a member of the House Natural Resources Committee and the longest-serving member of Congress.

Advertising

Advertising